The art of enchantment: the sirens & nymphs that inspired Those Fatal Flowers

Those of you who read my announcement post already know that the first iteration of THOSE FATAL FLOWERS began in a high school creative writing class. Throughout the nearly two decades that this story has been percolating, one thing remained constant: I never wanted my sirens to be of the mermaid variety, despite the fact that, these days, this is how they are nearly always portrayed. But more on that in a later post.

Before we get to the beautiful art, let me take a step back and share some of my personal history with my leading monster lady. It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when I first became aware of the concept of sirens. These are the handful that I can remember:

Disney’s Ariel technically fits the modern depiction, though Ursula, with her dark intentions, is arguably the closer match—a beautiful and dangerous woman armed with a seductive song.

For the millennials among us, there was an episode of So Weird that aired in 1999 where Fi saves Callie, a siren, from a predatory stage manager who forces her to sing in order to profit off of her.

At around eleven years old, I found Donna Jo Napoli’s middle grade book SIRENA, which tells the story of a siren who must make a man fall in love with her in order to obtain immortality. But even though SIRENA utilizes elements from Greco-Roman mythology, the titular character is indeed a mermaid.

And of course, who could forget Celaeno, the harpy from the movie The Last Unicorn? Though harpies and sirens come from different myths (Ovid, for the record, refers to harpies “human-vultures”), she was most certainly the first winged female monster to cross my path.

Celaeno quite possibly might have been the only one until sections of THE ODYSSEY were assigned to me in freshman English class.

First you will come to the Sirens who enchant all who come near them. If any one unwarily draws in too close and hears the singing of the Sirens, his wife and children will never welcome him home again, for they sit in a green field and warble him to death with the sweetness of their song. There is a great heap of dead men's bones lying all around, with the flesh still rotting off them.

I was, to put it simply, transfixed by this image. It had the same magic as Napoli’s novel, but whereas her mermaids’ intentions were misunderstood by the passing sailors, these sirens very much wanted to lure men to their deaths. I was desperate for more passages about them, but Homer’s sirens spend very little time on the page; they seem to exist only to serve as an example of Odysseus’ cunning (though it was actually Circe who tells him how to beat them, to give credit where it’s due). By blocking his crew’s ears with wax, Odysseus and his men are able to sail past the sirens’ isle without falling victim to their song. As quickly as the monstrous women appear on the horizon, they are left behind in the ship’s wake for good.

But those fleeting paragraphs weren’t enough, and so I went to Google. Though Homer left out their physical descriptions from his epic, other Greek writers and artists did not. I’ll admit, I was expecting mermaids. What I found surprised me: creatures with the faces of women and the bodies of birds.

The Siren Vase

Greek c. 475 BCE

And so when I began that fateful short story, this was the siren I chose to write. Years later, when I returned to that seed of an idea, her form hadn’t changed. The tale I was trying to tell didn’t have the need for a wide-eyed mermaid’s first adventure onto dry land. The character I wanted to create had a powerful, monstrous body—one she initially despises, but in a violent world, comes to value.

But the body of a siren isn’t an easy thing to describe, especially as a fairly visual person. Once again, I found myself returning to antiquity for guidance.

In their earliest depictions, sirens appear as birds with the faces of women.

Water jar (hydria) with siren attachment

Greek, late 5th century BCE

However, as time goes on, their shape shifts into the form Thelia and her sisters share—the body of a woman from the waist up, with the legs and talons of a bird and, of course, a resplendent pair of wings.

Siren with a Kithara from a Grave Monument

Greek, late 4th century BCE

Siren statue

Roman c. late 1st century CE

Ancient works gave me the form I was looking for, but they weren’t my only source of inspiration. Paintings from the Romantic movement helped me focus on the feelings I wanted to capture. Perhaps the best example of this is The Cave of the Storm Nymphs by Edward Poynter. Like Poynter’s nymphs, Thelia and her sisters store the treasures that wash ashore inside a sea cave. In one particular scene, the trio scours the beach for valuables to add to their hoard—though Thelia finds more than she’s bargained for.

The Cave of the Storm Nymphs

Edward Poynter, 1902

Although Odysseus doesn’t make an official appearance in THOSE FATAL FLOWERS, Waterhouse’s Ulysses and the Sirens served as inspiration for another scene where Thelia and her sisters descend on a ship to lure it into the reef surrounding their island home.

Ulysses and the Sirens

John William Waterhouse, 1891

William Etty’s sirens captured the nonchalance (and dare I say glee?) around the dead that I wanted mine to share.

The Sirens and Ulysses

William Etty, 1837

Teofil Kwiatkowski’s depiction shows the sirens as melancholic. I like to think that the center siren is Thelia’s sister Parthenope, whereas the dark-haired siren to her left has major Aglaope vibes.

Syreny

Teofil Kwiatkowski, 1845

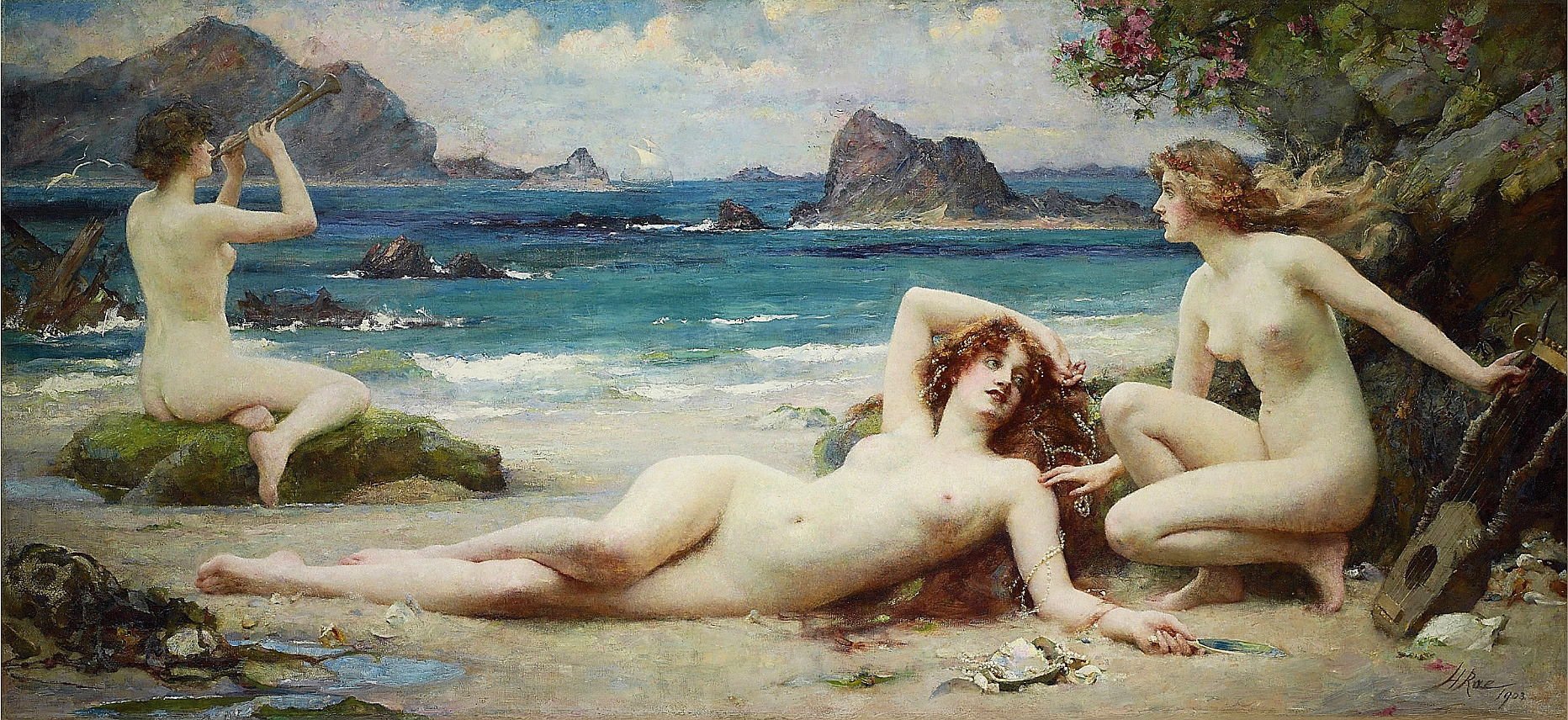

Looking at Henrietta Rae’s piece feels like peering in on that last moment of calm before a ship crystalizes on the horizon.

The Sirens

Henrietta Rae, 1903

John Longstaff provided inspiration for how I wanted sailors to experience my trio’s arrival.

Sirens

John Longstaff, 1892

But in a twist of fate, the most impactful painting to THOSE FATAL FLOWERS doesn’t depict a scene inspired by Greco-Roman myth at all—it comes to us from Russia, courtesy of Viktor Vasnetsov.

Sirin and Alkonost – Birds of Joy and Sorrow

Viktor Vasnetsov, 1896

This painting depicts two variants of winged women from Slavic myth—the sirin on the left (the bird of sorrow) and the alkonost on the right (the bird of joy). I was well underway with my first draft when I first found this painting. The broad strokes of Thelia’s story were already planned; she is a character who experiences an immense loss, and who’s entire arc is driven by the guilt she feels over it. Seeing the pain depicted on this sirin’s face was such a surreal experience for me because I found Thelia in it.

However the sirens have been depicted throughout history, one thing is always true: regardless of whether they are more bird or more woman, they are always monsters. But the emotions on display (here, despair, but also boredom, elation, longing) aren’t feelings that monsters are traditionally considered capable of experiencing. Godzilla never gets lonely; the xenomorph doesn’t express regret. Ultimately, that’s the impossible gray area I wanted to explore: at what point did the sirens stop being girls, and then women, before they became something else?

I don’t think there’s an easy answer to that question. If anything, the art only helps underscore that while they may have physically become monsters in a single devastating moment of magic, the human heart stubbornly remained.